- Greg Bear: I like to imagine taking a vacation on Mars

- He says the thin atmosphere and frigid temperatures make it a harsh environment

- After Earth, it's considered the most hospitable planet for life in the solar system, he says

- Bear: Scientists, writers and nerds have all been fascinated by the story of Mars

Editor's note: Greg Bear is an internationally bestselling science-fiction author of many books, including "Moving Mars," "Darwin's Radio" and "Hull Zero Three." As a freelance journalist, he covered 10 years of the Voyager missions at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

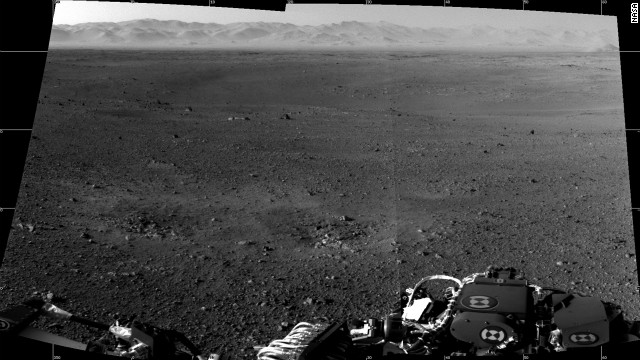

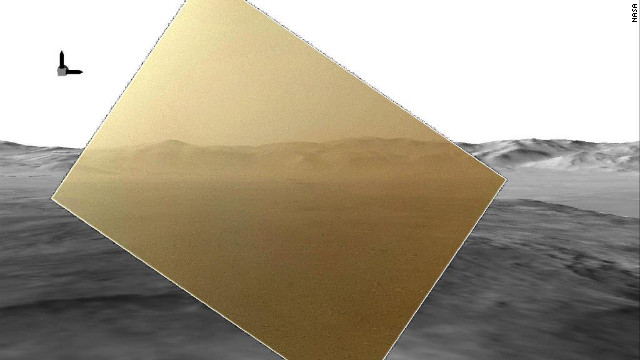

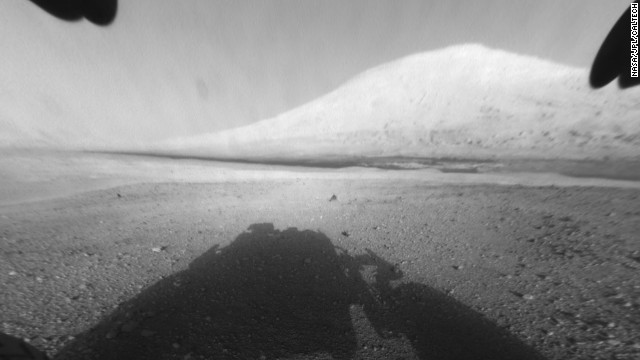

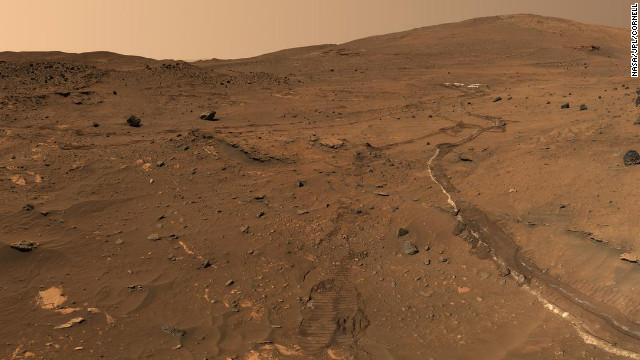

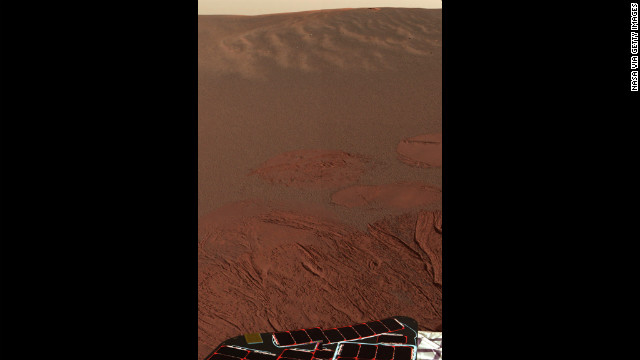

(CNN) -- Every now and then, I spend time on Mars. I dig my naked toes into the fine, red-orange soil, watch how it clings to my skin -- and feel an incipient itch. The iron-rich dust is pretty alkaline. The air -- or lack of it -- also makes me itch. Pretty soon, I'll break out in what the locals call "vacuum rose," as the blood boils in capillaries beneath my skin, because the air on Mars is pretty nearly a vacuum.

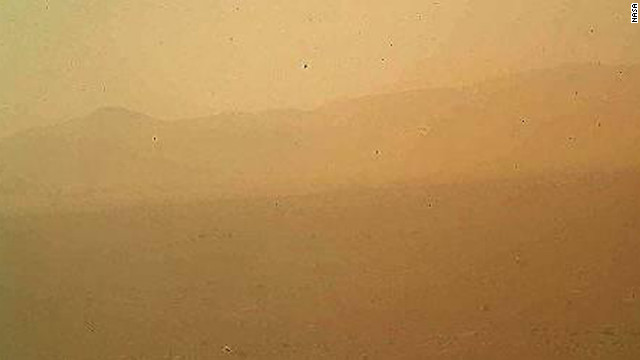

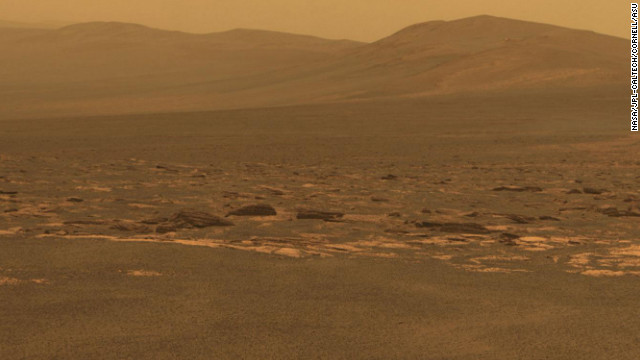

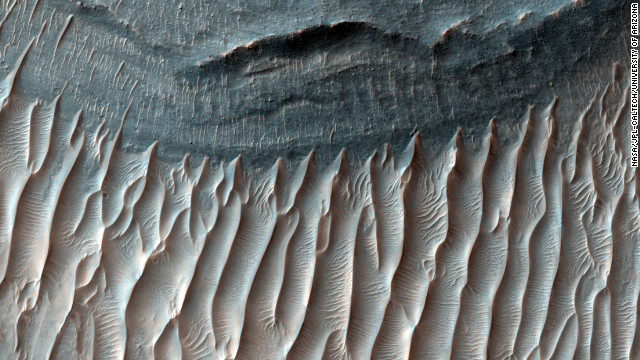

That doesn't mean the atmosphere can't kick up a planet-girdling storm when the weather is just right. Right now, as evening approaches, the sky is a dusty pink, tending to brown-black in the east. The sun is a brilliant disk in the west, one-third smaller than I'm used to on Earth and not nearly as warming. Feathery layers of dust fan out around the lowering sun, and a few smeared-out ice-crystal clouds glint silvery gray, but the rest of the sky is clear, and the stars above stand out brighter and sharper than night on Mauna Kea.

One of Mars' two moons, Phobos, or "Panic," named after one of the war-god's dogs, is little more than a big, tumbling rock. The second dog or moon is Deimos, "Terror." Phobos is blacker than sin, blacker than soot, but still visible to my naked, freezing eye. It's cold out right now, about -40 degrees Fahrenheit. Martians call this a balmy summer evening.

Tech: Internet explodes with joy over Curiosity

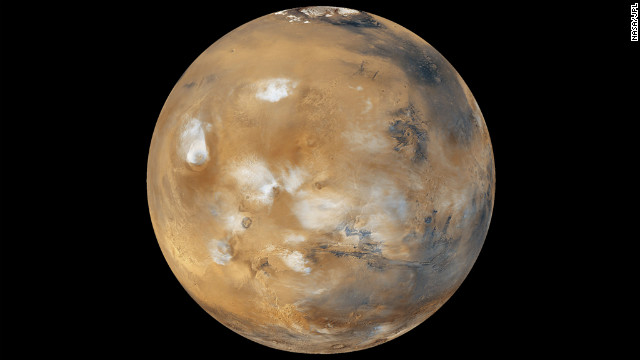

Of all the planets apart from Earth in our solar system, Mars is the most hospitable. Yeah. Right. Better keep my visit short. And yet, despite the discomfort, the danger, I love it here. I love coming back for these imaginary vacations. The sights are amazing.

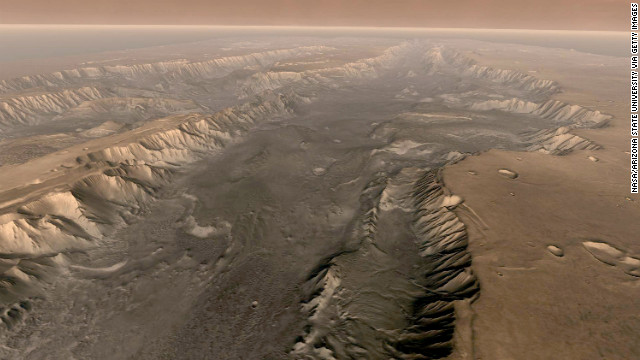

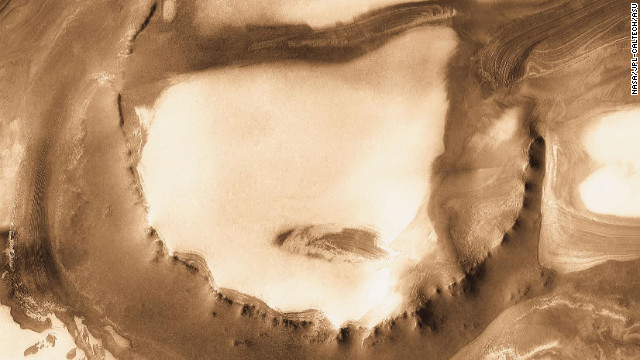

Trudging up the slope of Olympus Mons, the largest volcano in the solar system, you'll hardly notice the climb, it's so gradual. But by the time you've finished the 180-mile journey, you're about 14 miles higher than the datum -- what passes for sea level here. Fourteen miles. Mount Everest is about 5½ miles.

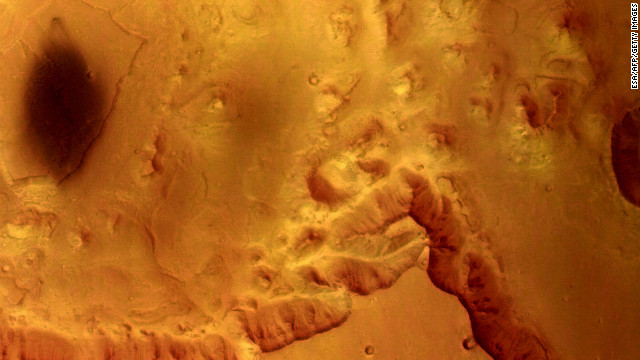

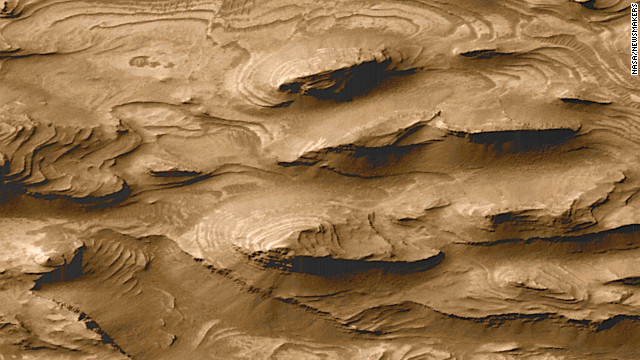

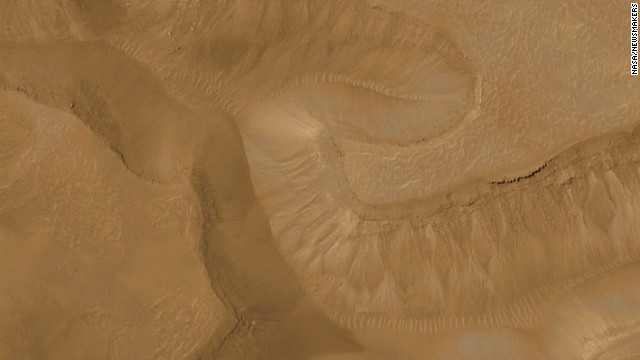

There are no seas. But once very likely there were seas, possibly big ones. Mostly shallow, basic and even fizzy, especially around out-gassing volcanic vents, all just right for potential extremophiles. Extremophiles are life forms that adore conditions we find harsh. For them, Mars could have been heaven.

And here's where the romance of Mars gets really good.

I'm going back in time. ... Can't stop myself. Jonathan Swift somehow guessed the correct number of Mars' moons (two). Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli saw what he described as "channels," or canali. Arizonan Percival Lowell, knowing a good PR move, then made "canali" into "canals."

H.G. Wells had us invaded by octopoid, blood-drinking Martians tired of living on their old, worn-out world.

Edgar Rice Burroughs upped the ante on Lowell's canals by populating the ancient red planet with gorgeous, oviparous princesses and warlike, four-armed green Martians.

In a few decades, Mars heated up.

News: Rover captures nearby rocket footprint

Ray Bradbury sealed the deal by making us all Martians. He sent us there; we stared into the water in the canals -- and our reflections, the faces of new Martians, stared back.

But not even Ray, back when he wrote "The Martian Chronicles," could have imagined how the real story might play out.

The "canals" aren't there any more. We can't find them, don't see them. But if evidence of Martian lakes and oceans pans out, Mars might have been hospitable to life hundreds of millions of years earlier than Earth. Earth was still cooling down from its natal heat, still barraged by asteroids, and life, if it developed at all here, was probably getting the crap kicked out of it on a regular basis. Starting over again and again from scratch, or not starting at all.

Until -- and this is just speculation, but it may have a foundation in fact -- until something big hit Mars and sprayed the seeds of Martian life across the gulf of space to land on Earth. Backwash. Martian spitballs.

We've analyzed small meteorites knocked loose from Mars. They fell onto Antarctica, and some scientists have taken the very controversial view that there is evidence of life in them. Not proven, not certain, but ...

Light Years: 5 reasons to be excited about Curiosity

My vacation on Mars could really be a homecoming. We may all be Martians. Wouldn't that be utterly cool to know? Scientists need to know. But you don't have to be a scientist to find the science of Mars compelling. Maybe an interest in genealogy will do.

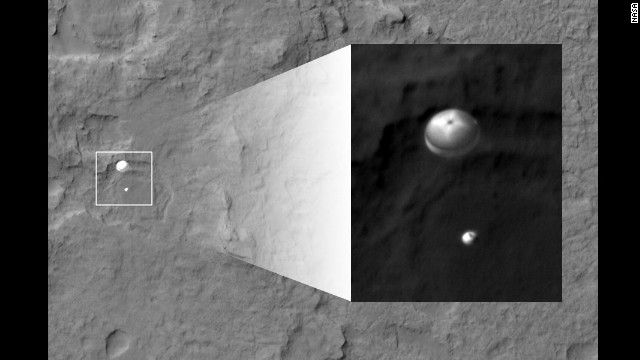

The challenge of getting to Mars is extreme. It's close as planets go, every now and then approaching less than 40 million miles to Earth -- but missions to Mars can spend months or years in space, depending on the economics and fuel load. Landing is tricky because aero-braking and parachutes are far less effective than in Earth's thicker atmosphere.

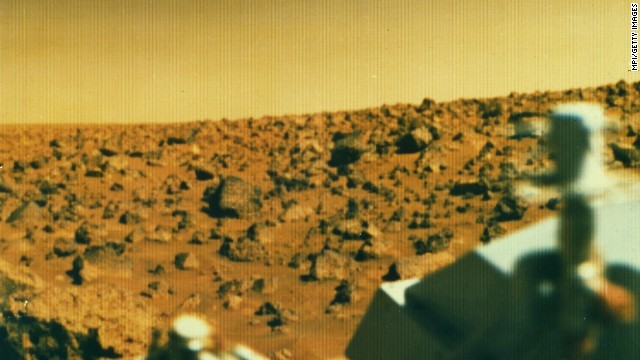

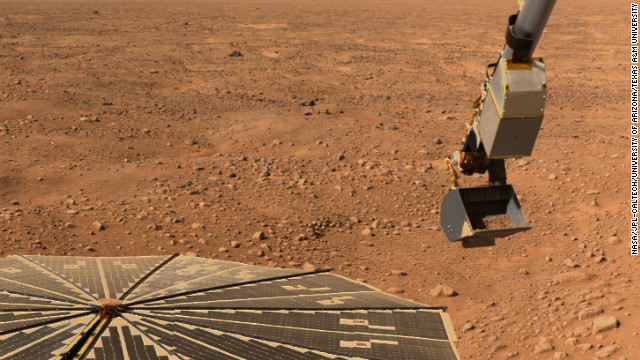

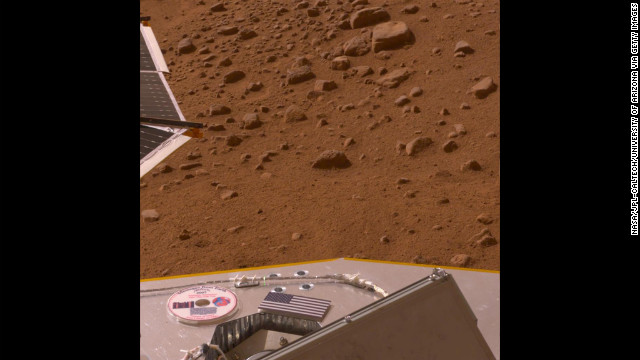

In the 1970s, the Viking landers came down on their own rockets, but they didn't carry rovers and looked around from a fixed position. Still, they sent us our first clear pictures of Mars from the surface.

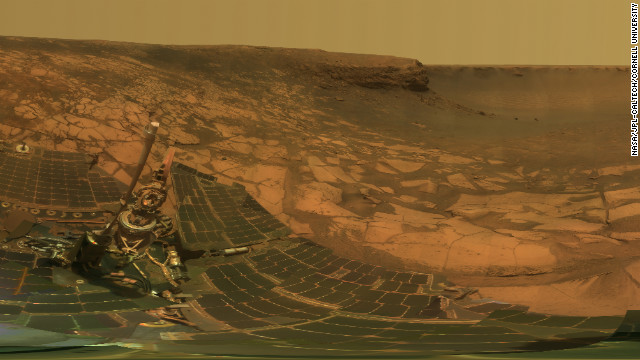

Engineers like making tough jobs look impossible, sometimes. In 1997, Pathfinder bounced down, literally, within a big cluster of very tough beach balls, which then deflated and released Sojourner, a cute-as-a-bug wandering robot. In 2004, Spirit and its twin, Opportunity, both came down bouncing as well.

News: Unmanned versus manned exploration

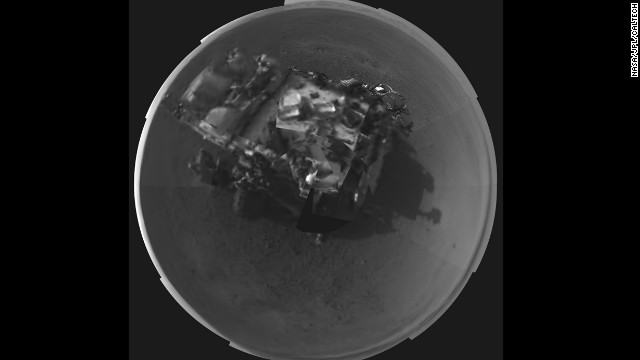

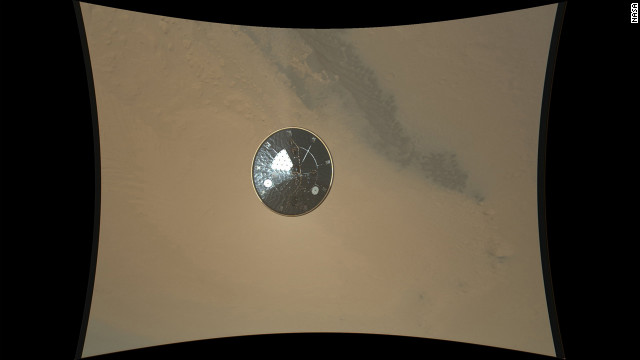

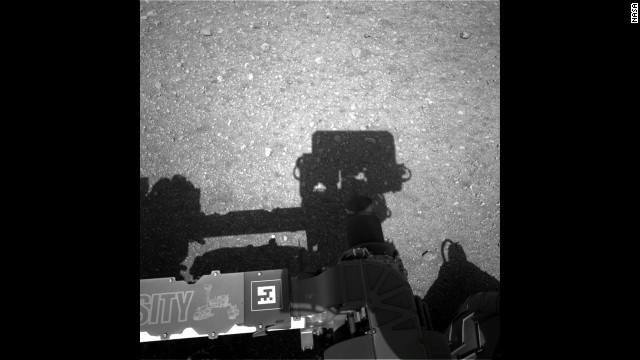

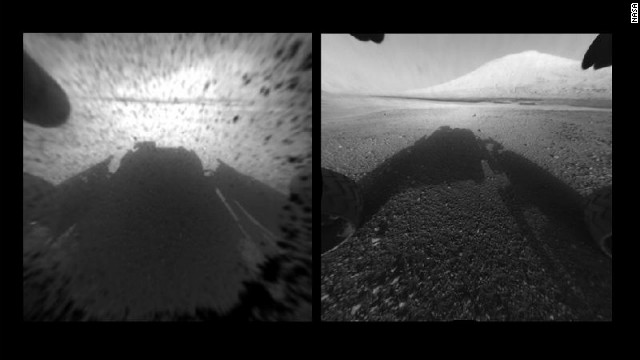

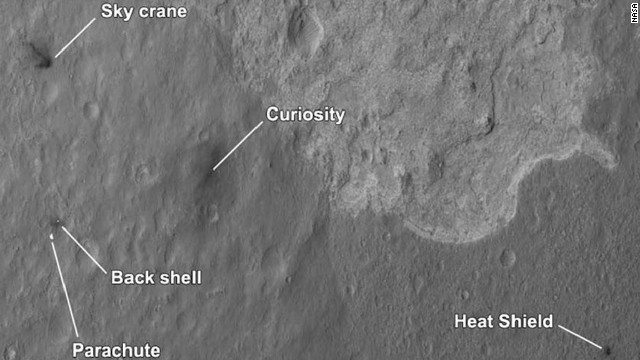

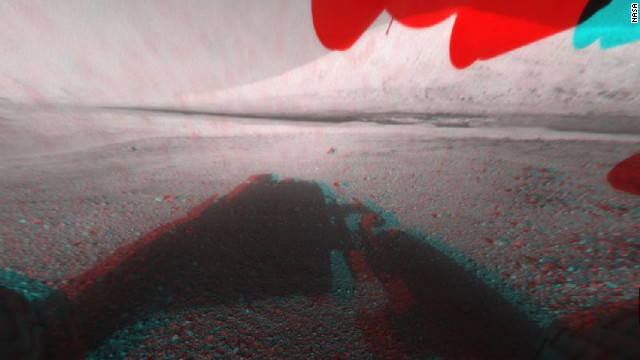

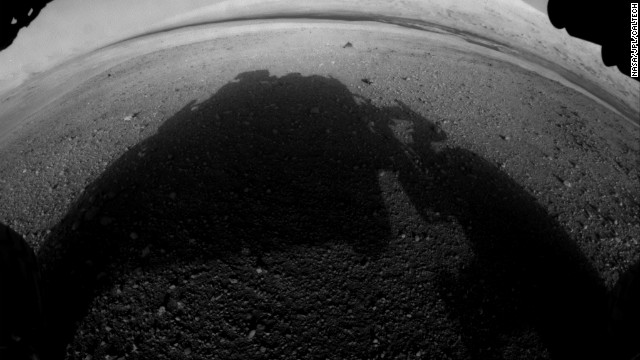

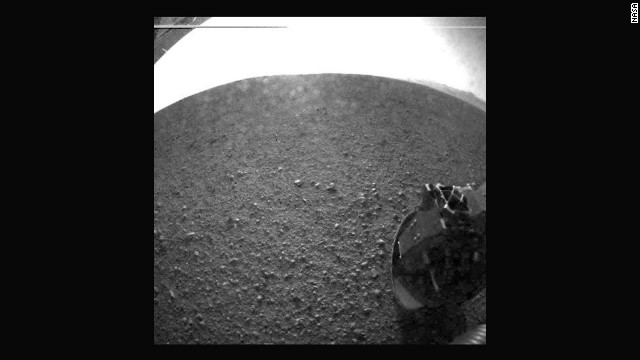

Curiosity, too large for that kind of landing, made its final descent winched from a Rube Goldberg, rocket-powered flying crane. But doubtless you know that story. The animation and videos are astonishing. And they're only going to get better.

Why do we capital-N Nerds love Mars so much?

Because it's beautiful, it's tough, it's buried in our mythic, childhood memories. It's covered with human triumphs but also with sad stories of failure. This time, the engineers and scientists are jubilant.

We're back, baby. Earth is definitely our mother, but maybe, just maybe, we're going to learn who's our papa.

It would be fun to be a Martian.

Follow @CNNOpinion on Twitter.

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion.

No comments:

Post a Comment